MOHAN GURUSWAMY:

Small states are a must for Better Governance.

Uttar Pradesh is larger in terms of population than Brazil, Japan or Bangladesh. The total population of India in 1947 was about 320 million and today, we have about that number of people who are below the poverty line.

The creation of Telangana, almost 60 years after the people of the region first voiced their misgivings about being co-opted into Andhra Pradesh, is yet another step in rationalising and restructuring the Union of States that India is meant to be. India was never meant to be a union of linguistic states, but a union of well governed and manged states. This creation in 2014 has fully justified itself when Telangana, once among the poorer agro-climatic zones in the country, posted the fastest SGDP growth and gained a place for itself among high per capita income states.

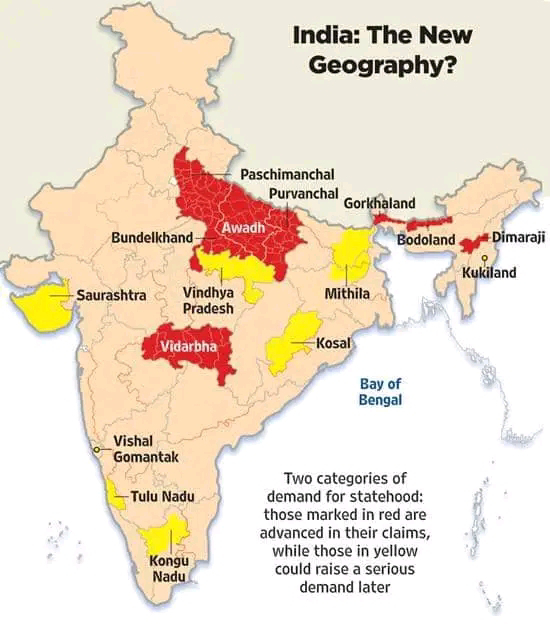

Thus, the demand for newer administrative units will be a continuous one, one that seeks to bring distant provincial governments in remote capitals closer to the people. The BJP has from time to time stated that it was in favour of a Vidharba state. BSP supremo Mayawati has several times expressed a view that Uttar Pradesh needs to be broken up into three or four states. Even in Tamil Nadu, Dr S. Ramadoss of the Pattal Makkali Katchi (PMK), a regional political party, had advocated the bifurcation of Tamil Nadu, with the northern districts being carved out to form a separate state.

Historically too, there is some basis to this as the Tamil-speaking region in the past had comprised of kingdoms centred around Kanchipuram and Tanjore-Madurai. The late J. Jayalalithaa had shrilly denounced this demand as “secession” when the PMK had only wanted a smaller state within the Indian Union. The Chennai-centred Tamil Nadu state we now know was the creation of the British. Similarly, Andhra Pradesh, Karnataka, Maharashtra, Gujarat and several other linguistic states have no historical basis. The yearning for linguistic sub-nationalism is a post-Independence phenomenon.

The biggest states of India -- Bihar, Madhya Pradesh, Rajasthan and Uttar Pradesh -- are also its worst-off states and hence the acronym “Bimaru” for them is most appropriate. They are also predominantly Hindi-speaking states, and hence quite clearly there is no linguistic or historical basis for their creation and existence as they are. Yet within their blanket linguistic conformity, these states cover a vast diversity of distinct regions, with characteristic commonly spoken languages, culture and historical traditions. Each of these states, either in terms of land mass or population, would still be much larger than many countries in the world. Uttar Pradesh is larger in terms of population than Brazil, Japan or Bangladesh.

The late Dr Rasheeduddin Khan had most eloquently made out this case; of Hyderabad I would like to add, way back in April 1973 in Seminar, which was at that time edited by the late Romesh Thapar. He had India divided according to its 56 socio-cultural sub-regions and a map showing these was the centrepiece of the article. That picture still remains embedded in my mind, and whenever I think of better public administration that map would always appears.

The Seminar map is a veritable blueprint for the restructuring of India. Out of UP and Bihar eight distinct sub-regions are identified. These are Uttaranchal, Rohilkhand, Braj, Oudh, Bhojpur, Mithila, Magadh and Jharkhand. The first and last of these have now become constitutional and administrative realities. But each one of the other unhappily wedded regions is very clearly a distinct region with its own predominant dialect and history. For instance, Maithili spoken in the area around Darbhanga in northern Bihar is very different from Bhojpuri spoken in the adjacent Bhojpur area. Similarly, Brajbhasha in western UP is quite different from Avadhi spoken in central UP. India’s largest state in terms of area, Madhya Pradesh, is broken into five distinct regions; Rajasthan, Gujarat and Maharashtra into four each, Andhra, West Bengal and Karnataka into three each, Tamil Nadu, Kerala and Odisha into two each, and so on.

Since 1971, India’s population has doubled to cross 1.3 billion. Even at constant prices (1980-81), GNP has grown by 10 times, to the equivalent of $2.62 trillion. In 1971 the total money supply was Rs 11,019 crores, but it has now grown to over Rs 24 lakh crores. Naturally, the size and scope of government has also changed. The 1980-81 Budget of the Government of India was a mere Rs 19,579 crores. It is now around Rs 20 lakh crores. The annual budgets of state governments too have grown likewise.

The total population of India in 1947 was about 320 million. Today, we have about that number of people who are below the poverty line. In the meantime, India has become a very youthful country, with 70 per cent of its people below 30, of whom about 350 million are below 14. Clearly, the task of government is not only much more enormous, but much more complex when the rising expectations, impact of new technologies and demographic changes are factored in. Our record so far is a cause for great concern and is a severe indictment of the failure of the system of governance in India.

That “the nature of the regime determines the nature of the outcome” is a well-known adage in public administration and public policy studies. The nature of a regime is not only influenced by its constitution, guiding philosophy and the consequent system of government, but also by the structure of the system. We know from experience, both in the corporate world and in public administration, that monolithic and centralised structures fail when the size and scope of the organisation grows. In public administration, this is called decentralisation. Decentralisation not only implies the downward flow of decision-making but also greater closeness of the reviewing authority to the decision-making level.

Thus, if more decision-making flows to the districts and sub-districts, the state government, which is the reviewing authority, must also have fewer units to supervise. I have always held that the real concentration of power is not with the Union government but with state governments. From the perspective of good governance, this is clearly unacceptable.

The “Report of the States Reorganisation Commission, 1955” states: “Unlike the United States of America, the Indian Union is not an indestructible union composed of indestructible states. But on the contrary the Union alone is indestructible, but the individual states are not.” It will be unfortunate if demands for the restructuring of India by creating more states are seen only as mere political contests, where the just causes of individual socio-cultural and agro-climatic regions is just a weapon of in the hands of out-of-work politicians deprived of a share of the benefits of office

Comments

Post a Comment